Page 42 [42]

happen in these previous relationships, namely, a certainty that

is equal to its truth, for certainty is, to itself, its object, and con¬

sciousness is, to itself, the true.” (Ibid)

Self-consciousness is thus an act of self-identification with itself,

whose insight and action is the already-mentioned the intellectual

perception. None of this is an achieved, received, closed, and final

state, but is rather a process characterized by constant dynamism.

In this process, two sides oppose each other: the real and the ideal,

objective-subjective, restricting and unrestricted. The tension of

these sides implicates the inner struggle of the inner sides of a

human. Froma global perspective, of course, this process does not

only take place at the abstract, generalized level, but can be traced

throughout history in the schema of everything. This is because

these moments are representative of each period, and philosophy

itself becomes the story of self-consciousness.

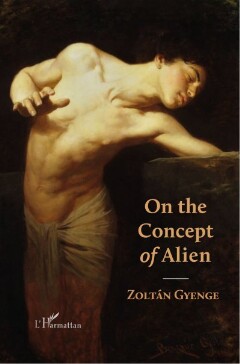

Narcissus is far from having self-consciousness and thus a self

as a result of which we could perceive him perceived as an individ¬

ual. This is because the individual is the same found in the other.

Narcissus, however, is a radical rejection of the other. As such,

he is far from being free. The unfortunate young man wanders,

longing for cognition, but unable to receive it. Because there is no

one else (no other) to get it from. He does not realize that the other

proceeds from him, and he could become a real being by the other.

Thus the shadow of existence remains.

The history of self-consciousness plays a special role in Hegelian

philosophy. At the level of absolute knowledge, we are talking about

a special experience becoming real. The spirit achieves absolute

knowledge by stepping beyond each of the phenomenal layers of

cognition and, at the same time, reaches the experience that the

self-reflection or self-immersion of the spirit is technically a im¬

mersion into the night of self-consciousness; but at the same time