Seite 53 [53]

TEMPLE AND MUSEUM. AN AMBIVALENT RELATION

“T believe that of over 2000 monasteries, very few are left, one of which is Erdene

Dsuu. Gombo gur has promised to guard Erdene Dsuu until its last half brick.

I think today’s Erdene Dsuu only still exists thanks to Gombo gur.’?

Another case of a local museum situated in a historical former monastery complex is

the Museum of Arkhangai Province in former temples of Dsaya Gegeen’s Monastery,

Monastery. The three temple buildings of the Lawran came under the protection

of Arkhangai Province in 1971 and under state protection in 1994. Since 1947

religious artefacts collected from all over the province had been stored in the San¬

dui Khuwilgaan Temple which turned into a “Local Study Office of the Province.”

In 1967 the Local Museum of Arkhangai Province was founded and parts of the

collections moved to the Eastern Semchin Temple.'°

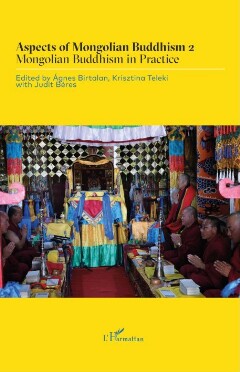

Gandantegchenlin Monastery in Ulaanbaatar was for years the only officially

active monastery, in fact since 1944 more a living museum under state control. In

contrast to the examples mentioned, the Bogd Khaan Palace with its adjunct temple

buildings had turned to a museum already after the death of the Bogd Khaan (1924)

in 1927. In the communist period, turning sacred buildings into museums and clas¬

sifying Buddhist monasteries and temples as cultural monuments was a way of

saving them as officially secular buildings, sometimes as anti-religious museums.

On the surface the form of the Buddhist temple architecture remained, sometimes

part of the “content” was converted into profane museum collections, the spiritual

— monks, deities and spirits — expelled. Believers turned into official non-believers

or simply museum visitors.

Re-sacralisation and Social Memory

After the turn to a democratic system in 1990 and several decades as museums, some

of the historically sacred buildings became active temples or monasteries again.

Mongolian Buddhist belief was kept alive in social and body memory.

In April 1990, by a ministrial resolution Erdene Dsuu Monastery resumed reli¬

gious service to function as a temple. A big opening ceremony took place in one of

the buildings, the Dalai Lama Temple, which until then had been the office of the

museum director or guardian. Monks conducted religious services in this building

until September of the same year. Thereafter they transferred to their current location,

the Lawran Temple. An attempt to return a museum to a temple was also made in

Choijin Lama Temple Museum. A group led by the well-known democratic activist

Lama Baasan, collected donations for the re-establishment of a religious association,

without success. At the same time, the Arkhangai Province Museum in Tsetserleg

° Khamba Lama Kh. Baasanstiren, Erdene Dsuu Monastery, 17 June 2015.

'0 Cf. Charleux, I.: History, Architecture and Restoration of Zaya Gegeenii Khiiree Monastery in Mon¬

golia. In: Zaya Gegeenii Khiiree: History, Architecture and Restoration of a Monastery in Mongolia.

Ed. by Isabelle Charleux. Bulletin du Musee d’ Anthropologie Prehistorique de Monaco, 5. Monaco

2016, p. 20.

51