OCR

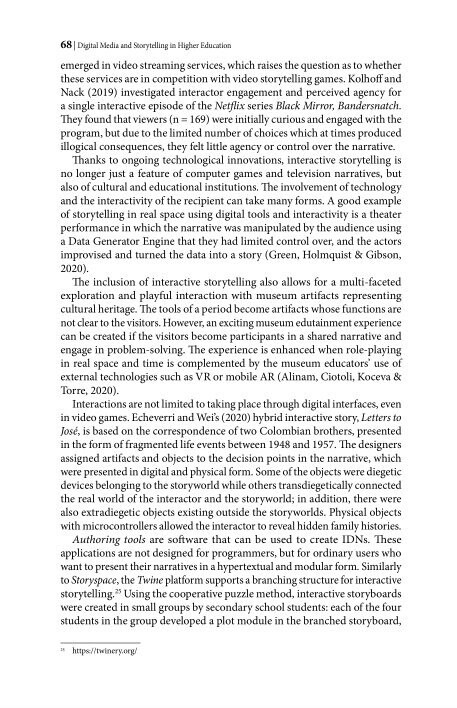

68 | Digital Media and Storytelling in Higher Education emerged in video streaming services, which raises the question as to whether these services are in competition with video storytelling games. Kolhoff and Nack (2019) investigated interactor engagement and perceived agency for a single interactive episode of the Netflix series Black Mirror, Bandersnatch. They found that viewers (n = 169) were initially curious and engaged with the program, but due to the limited number of choices which at times produced illogical consequences, they felt little agency or control over the narrative. Thanks to ongoing technological innovations, interactive storytelling is no longer just a feature of computer games and television narratives, but also of cultural and educational institutions. The involvement of technology and the interactivity of the recipient can take many forms. A good example of storytelling in real space using digital tools and interactivity is a theater performance in which the narrative was manipulated by the audience using a Data Generator Engine that they had limited control over, and the actors improvised and turned the data into a story (Green, Holmquist & Gibson, 2020). The inclusion of interactive storytelling also allows for a multi-faceted exploration and playful interaction with museum artifacts representing cultural heritage. The tools of a period become artifacts whose functions are not clear to the visitors. However, an exciting museum edutainment experience can be created if the visitors become participants in a shared narrative and engage in problem-solving. The experience is enhanced when role-playing in real space and time is complemented by the museum educators’ use of external technologies such as VR or mobile AR (Alinam, Ciotoli, Koceva & Torre, 2020). Interactions are not limited to taking place through digital interfaces, even in video games. Echeverri and Wei’s (2020) hybrid interactive story, Letters to José, is based on the correspondence of two Colombian brothers, presented in the form of fragmented life events between 1948 and 1957. The designers assigned artifacts and objects to the decision points in the narrative, which were presented in digital and physical form. Some of the objects were diegetic devices belonging to the storyworld while others transdiegetically connected the real world of the interactor and the storyworld; in addition, there were also extradiegetic objects existing outside the storyworlds. Physical objects with microcontrollers allowed the interactor to reveal hidden family histories. Authoring tools are software that can be used to create IDNs. These applications are not designed for programmers, but for ordinary users who want to present their narratives in a hypertextual and modular form. Similarly to Storyspace, the Twine platform supports a branching structure for interactive storytelling.” Using the cooperative puzzle method, interactive storyboards were created in small groups by secondary school students: each of the four students in the group developed a plot module in the branched storyboard, % https://twinery.org/

Szerkezeti

Custom

Image Metadata

- Kép szélessége

- 1831 px

- Kép magassága

- 2835 px

- Képfelbontás

- 300 px/inch

- Kép eredeti mérete

- 1.38 MB

- Permalinkből jpg

- 022_000040/0068.jpg

- Permalinkből OCR

- 022_000040/0068.ocr

Bejelentkezés

Magyarhu